Constant Models

When predicting outcomes using machine learning it’s always useful to have a baseline to compare results against. A simple baseline is the best constant model; that is a model that gives the same prediction for any input. This is a really simple check to perform against any dataset, and can be informative to check across validation splits.

There are simple algorithms for finding the best constant model. For categorical predictions just evaluate every possible category to choose as the constant prediction. For continuous predictions with a convex loss function you can use bisection, starting with the smallest and largest values of the predictor. For common loss functions the best constant model is a familiar measure of central tendency.

| Loss Function | Best constant | Minimum Value |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Mode | Maximum proportion |

| Cross Entropy | Proportion | |

| Root Mean Squared Error | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| Mean Absolute Error | Median | MAD median |

| Mean Weighted Absolute Error | Quantile | |

| Maximum Absolute Error | Midrange | Half the range |

This is useful to know when using piecewise constant models (like decision trees) because on each piece they will use these best constants. The rest of this article will explain these examples in detail and end with a general family of loss functions that covers many use cases.

Accuracy

For predicting which category an object is in the most common metric is accuracy. The accuracy of constantly predicting a category is the number of items which have that category divided by the total number of items. The best constant model predicts the most common category (the mode), and the accuracy is the proportion of items in the most common category.

A claim like a model is 85% accurate may sound impressive, but if the most common category covers 83% of cases it’s probably not a great achievement. There are different metrics (like ROC AUC) and sampling methods (like balanced resampling) that can remove this advantage to predicting common cases, but just being aware of the best constant accuracy is helpful in understanding how much better a model is performing.

Cross Entropy

A more discerning metric for categorical data is the cross-entropy. If P is a N x C matrix of the probabilities of each of the C categories and y are the actual categories, as a one-hot encoded C x N matrix, then the probability for the actual category is pred_prob = apply(P * y, 1, sum). The cross-entropy is just the sum of the logs of the predicted probabilities for the actual categories, sum(log(pred_prob)).

The best constant 1 x C vector here is where each category is just the number of times it occurred divided by the total number of occurrences. That is apply(y, 2, sum) / sum(y); and the value is then just the log of the probability of the outcome.

In the special case of binary classification, when C is 2, we can just focus on the case of positive outcomes. Then given a 0-1 encoded y, the best constant is p = sum(y)/length(y), and the cross-entropy is length(y) * (p * log(p) + (1-p) * log(1-p)).

Root Mean Squared Error

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is the most common measure for regression problems. The best constant model is the mean of the values, and its RMSE is the standard deviation.

This is because the mean is the unique point whose differences from each data point sum to zero. Let’s denote our vector of data points as x, the mean as xbar, the standard deviation as sd and our constant prediction as a. Then the mean satisfies sum(x - xbar) == 0 (which is just a rearrangement of the standard definition xbar = sum(x) / length(x)). The RMSE is given by rmse(a) = sqrt(mean((x - a)^2)). Expanding the quadratic around the mean gives:

rmse(a) == rmse((a - xbar) + xbar)

== sqrt((a - xbar)^2 + 2*(a - xbar)*mean(x - xbar) + mean((x - xbar)^2))Since the middle of the sum term vanishes by definition of the mean, this leaves

rmse(a) = sqrt((a - xbar)^2 + mean((x - xbar)^2))

In mathematical notation

\[\sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{i=1}^{N} (x_i - a)^2} = \sqrt{(a - \bar{x}^2) + \frac{1}{N} \sum\limits_{i=1}^{N}(x_i - a)^2}.\]

Looking at this formula it’s clear that the root mean square error is minimum at the mean, and at the mean it’s value is sqrt(mean(x-xbar)^2), which is the definition of the standard deviation.

It’s actually common to use the constant model as a benchmark in this context; in terms of the coefficient of determination, or more commonly R². It is defined as R2 = 1 - (RMSE / sd)^2, where sd is the standard deviation. So the best constant model has an R² value of 0, any better model has a positive value and a perfect model (with 0 RMSE) has a value of 1. Note that it’s possible to have a negative R² value if the prediction is worse than the mean.

Mean Absolute Error

The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) is a robust measure for regression; it’s not sensitive to outliers. The best constant prediction is the median of the values.

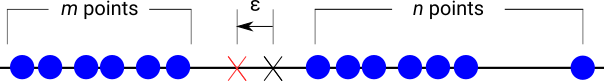

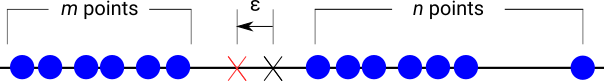

To see why this is consider how the MAE, which is the average of the absolute distances, changes as we move the constant prediction point. As in the diagram below we have m data points to the left of our “test point” and n data points to the right.

As we move a distance ε to the left (without crossing any data points) the constant prediction is ε closer to each of the m points on the left, and ε further from each of the n points on the right. So the mean average error changes by ε * (n - m) / (n+m). This is decreasing as long as we’re moving the prediction towards more points (m > n), and will be minimal when m = n. So the minimum occurs when there are an equal number of data points to the left or the right, which is the median.

Note that there is some ambiguity here when the number of points is even. For example in the dataset 1, 2, 3, 4 any number between 2 and 3 will minimise the MAE; typically we take the midpoint 2.5.

The minimum value of the MAE isn’t so familiar, it’s the Mean Average Deviation of the median (or MAD Median for short). However it’s a useful benchmark; analogous to the coefficient of determination we could consider a measure like 1 - MAE / mad_median to assess improvement over the constant model.

Mean Weighted Absolute Error

Sometimes in prediction tasks it’s better to conservatively over- or under-predict to temper expectations. One way to do this is to penalise errors in one direction greater than errors in the other. The Mean Weighted Average Error applies this to the MAE:

mwae(w, a) = w * (x >= a) * (x - a) - (1 - w) * (x < a) * (x - a)

\[\rm{MWAE(a; w)} = \frac{1}{N} \sum\limits_{i=1}^{N} \begin{cases} w (x_i - a) & x_i \geq a \\ (1-w) (a - x_i) & x_i \lt a \end{cases}\]

The constant model that minimises MWAE is the wth quantile. To understand why, as with MAE, consider how the MWAE changes as the prediction moves a distance ε towards m points away from n points.

Then the prediction is ε further from n points which increases MWAE by w * n * ε / (m + n) and ε further from m points which decreases MWAE by (1 - w) * m * ε / (m + n). This will be minimised when the two changes balance; when we can’t decrease it by moving in one particular direction (because MWAE is convex). This happens when w * n == (1 - w) * m, that is when w == m / (m + n). So it’s minimised when the fraction of data to the left of the test point is w. In particular when w = 0.5 then MWAE == MAE / 2 and the best constant model is the median.

Note that again this is ambiguous; we can treat it the same way as the median by averaging the minimiser of quantiles taken from limits above and below.

Generalisation: Lᵖ Error

Almost all of these example metrics are a special case of a weighted Lᵖ error. The Lᵖ error is given by

lp(a) = mean((x - a)^p) ^ (1/p)

\[L^p(a) = \sqrt[p]{\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{i=1}^{N} {\left\Vert{x_i - a}\right\Vert ^p}}\]

In particular when p is 1 we get the Mean Average Error and when p is 2 we get the Root Mean Square Error.

As \(p \rightarrow \infty\) this converges to the maximum norm: l_infinity(a) = max(x - a). This depends only on the furthest points, and is minimised at the midrange, halfway between the maximum and minimum point, and the minimum value is half the range. There are a whole range of metrics between the MAE at \(p=1\), which is completely insensitive to outliers, and the Maximum Norm at \(p = \infty\) which depends only on the most extreme outliers. As p increases the best constant moves continuously towards the outliers.

We can further generalise this by weighting the norm as we did for MWAE:

weighted_norm(w, x) = sum(w * (x >= 0) * x - (1 - w) * (x < 0) * x)

\[\left\Vert x \right\Vert_w = \sum\limits_{i=1}^{N} \begin{cases} w x_i & x_i \geq 0 \\ -(1-w) x_i & x_i \lt 0 \end{cases}\]

It’s also possible to generate the trimmed mean or Winsorized mean by modifying how the metric treats the most extreme points; removing or capping the most extreme values. There are certainly metrics that don’t fit in this framework, but this connection between a metric and best constant statistic gives simple benchmarks to common models and suggests a family metrics for different regression problems.

Next time you look at any predictive model first ask: “How much better is this than the best constant model?”